Christopher Stocks

Journalism

- Madresfield | House & Garden

- Winfield House | Gardens Illustrated

- Naming of Names | Independent on Sunday

- Tessa Kennedy | House & Garden

- USCS | Abercrombie & Fitch Magazine

- Armageddon Calling | Wallpaper

- Beverley Nichols | Gardens Illustrated

- Deep in the Forest | Tank

- Dorset | Daily Telegraph

- Peyton Skipwith | B.B,Esquire

- Seeds | Patek Philippe

- Tenants of the National Trust | NT Magazine

- Emeco | Broom chair

- Flucked | Empire

- Space Oddity | The Face

- Cleopatra | Harpers

- Pebbles | Things magazine

Tessa Kennedy | House & Garden

Go through an arch on a small back street in Knightsbridge, squeeze between a row of million-pound cottages, and there, looming ahead, is a large early 19th-century house, for all the world like something out of Great Expectations. We’re only a stone’s throw from Harvey Nichols, but it’s eerily quiet. Double doors lead to a double flight of stairs, at the top of which is the spectacularly theatrical flat in which the interior decorator Tessa Kennedy has lived since 1992.

Kennedy is a legendary figure in the world of interior design. Born in 1938 into a wealthy Scottish-Croatian family, she has lived an extraordinary life and worked for some of the richest and most demanding clients in the world. Drinking tea from a cafetière with her on a disconcertingly pneumatic Victorian sofa from Elveden, she explains how ‘I never saw my parents until I was five. I was shipped off to New York for the duration of the War and loved being there, so it was a shock to come back to London and rationing and these strange people who turned out to be my parents.’

At the age of 18 she ran away with Dominick Elwes, the 26-year-old son of a society portraitist, but her father took such a dim view that he instituted legal proceedings to prevent them marrying. Overnight it became a cause celèbre, and they fled, pursued by half the world’s press, via Scotland to Cuba, where they wed in January 1958. ‘We had a wonderful time,’ Tessa recalls, ‘until the Revolution came along and we had to escape on a raft with a pair of journalists from National Geographic. When we got back to England, Dominick was imprisoned for abducting a minor – me – and I was made a ward of court.’

Her move into interior decoration happened almost by chance. After his release from Brixton, Dominick became an editor and publisher, and in 1963 he launched Britain’s first full-colour directory of interior designers, among whose alumni were the young Davids Mlinaric and Hicks. When his friend Jimmy Goldsmith came looking for someone to redesign a hotel, Dominick recommended Mlinaric, but it was too big a job for Mlinaric on his own. ‘How about getting Tessa to help out?’ someone suggested, and Tessa – stuck at home with three young sons – leapt at the chance. It was an auspicious start, and in 1968, after winning a competition to redecorate the Grosvenor House hotel, she set up on her own.

Much-lauded schemes followed for Claridges and the Ritz, as well as private commissions for clients ranging from Eric Clapton and the late George Harrison (at the fabled Friar Park) to King Hussein of Jordan and the colourful Prince Jefri of Brunei, for whose Park Lane apartment she designed a revolving drawing room. Her work at the Ritz bar and casino proved a particularly useful calling-card. ‘They’re public spaces, which helps,’ she says, ‘and for the casino I designed an Amber Room that was twice the size of Catherine the Great’s – I suspect many of my Russian commissions came through that.’ A second marriage, to the film producer Elliott Kastner, added Hollywood royalty to the mix, as attested by snapshots of Tessa exchanging grins with the likes of Paul Newman and Marlon Brando.

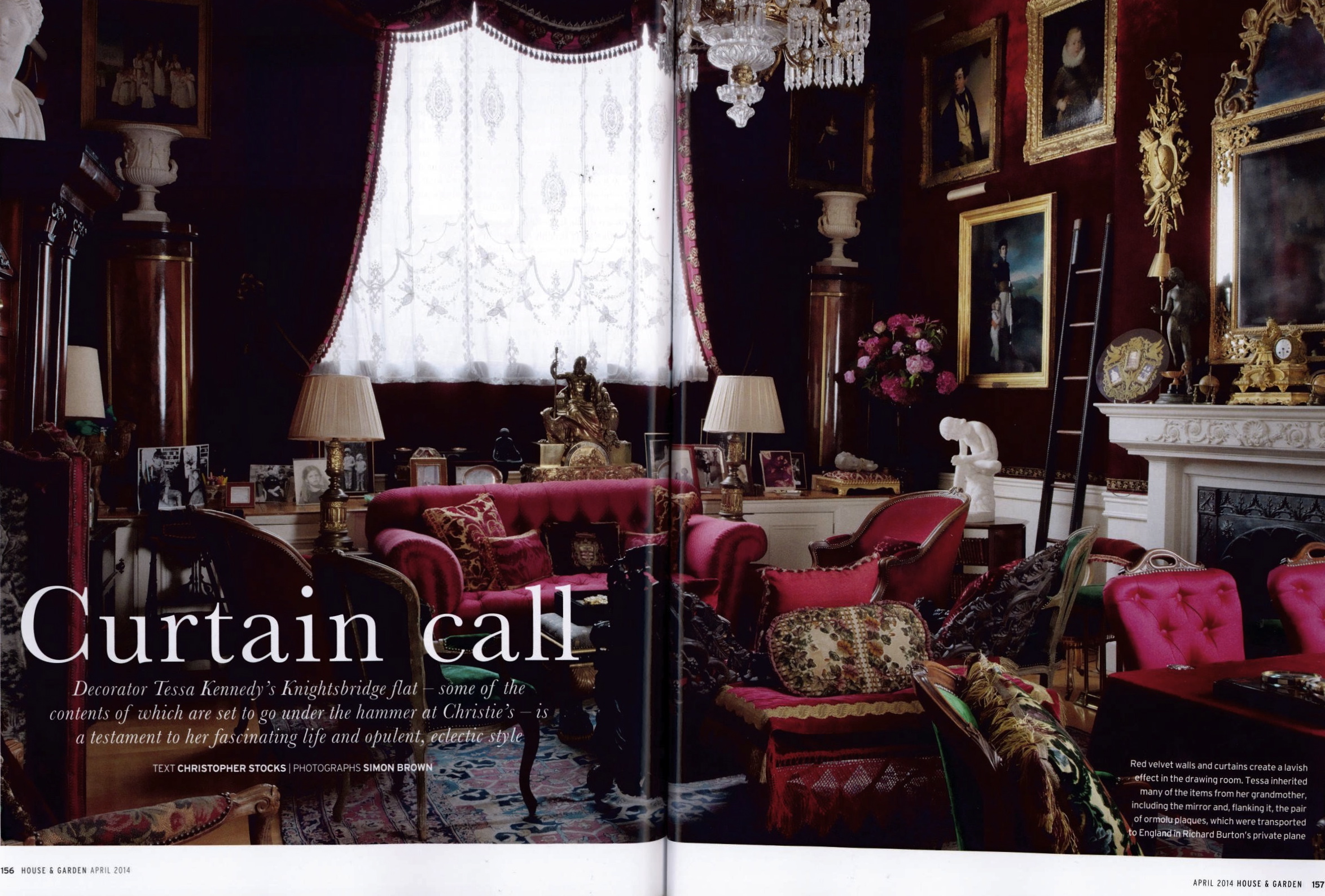

Her style is eclectic, opulent and leavened with a healthy dose of (often Catholic) kitsch, brilliantly exemplified by her flat, which has two huge rooms (the drawing room and master bedroom) and three tiny ones (the guest bedroom, dining room and kitchen), opening off a small square hall. This was originally an odd, awkward space, lit by a high window, but Tessa hung the walls with a striped taffeta from Lelievre and made a tented roof out of translucent silk dress fabric, filtering the daylight into a rosy glow.

To the right of the entrance is the red velvet-walled drawing room, stuffed with richly upholstered furniture and mementoes from Tessa’s family and friends. Every object has a tale to tell, like the ormolu plaques above the fireplace, which belonged to her grandmother, a shipping heiress who lived in Monte Carlo and counted Prince Rainier among her friends. ‘The plaques were from her yacht, but they were so heavy I couldn’t think how to get them back to London, until Richard Burton said, “I’ve got use of a private plane, so why not borrow that?”’

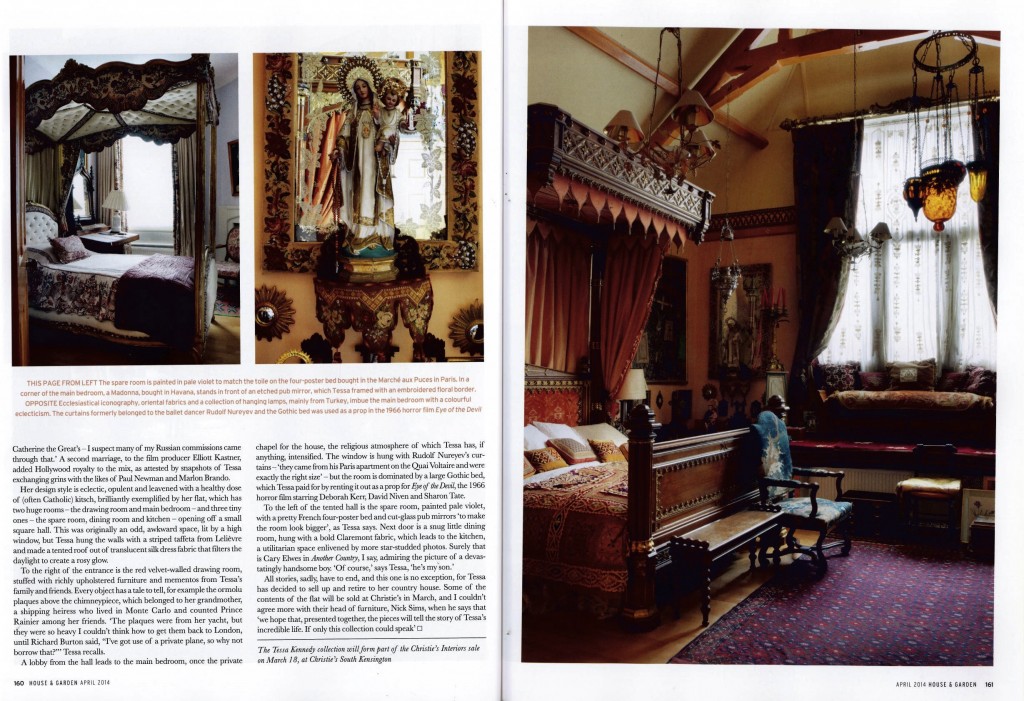

A lobby from the hall leads to the master bedroom, once the private chapel for the house, whose religious atmosphere Tessa has if anything intensified. The window is hung with Rudolf Nureyev’s curtains (‘they came from his apartment on the Quai Voltaire and were exactly the right size – a miracle!’), but the room is dominated by an enormous Gothic bed, which Tessa paid for by renting it as a prop for The Eye of the Devil, the 1966 horror film starring Kim Novak, David Niven an d Sharon Tate.

d Sharon Tate.

To the left of the tented hall is the guest bedroom, painted pale violet, with a pretty French four-poster bed and cut-glass pub mirrors ‘to make the room look bigger,’ as Tessa says. Next door is a snug little dining room, hung with a bold Claremont toile, which leads to the kitchen, a utilitarian space enlivened by more star-studded photos. Surely that’s Cary Elwes in Another Country, I say, admiring the picture of a devastatingly handsome boy. ‘Of course,’ says Tessa, ‘he’s my son.’

All stories, sadly, have to end, and this one is no exception, for Tessa has decided to sell up and retire to her country house. Many of the contents will be sold at Christie’s in March, and I couldn’t agree more with their head of furniture, Nick Sims, when he says that ‘we hope that, presented together, the pieces will tell the story of Tessa’s incredible life. If only this collection could speak.’

© Condé Nast 2014