Christopher Stocks

Journalism

- Madresfield | House & Garden

- Winfield House | Gardens Illustrated

- Naming of Names | Independent on Sunday

- Tessa Kennedy | House & Garden

- USCS | Abercrombie & Fitch Magazine

- Armageddon Calling | Wallpaper

- Beverley Nichols | Gardens Illustrated

- Deep in the Forest | Tank

- Dorset | Daily Telegraph

- Peyton Skipwith | B.B,Esquire

- Seeds | Patek Philippe

- Tenants of the National Trust | NT Magazine

- Emeco | Broom chair

- Flucked | Empire

- Space Oddity | The Face

- Cleopatra | Harpers

- Pebbles | Things magazine

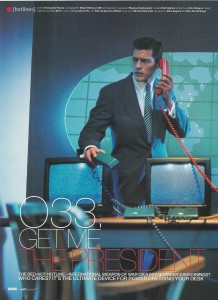

Armageddon Calling | Wallpaper

What is it that makes the idea of a hotline so… hot? One of the most potent twentieth-century symbols of absolute power, the hotline has come to occupy a unique niche in the collective unconscious somewhere between Lieutenant Uhura and the Roswell Incident. The difference being that hotlines are real. Or are they?

What is it that makes the idea of a hotline so… hot? One of the most potent twentieth-century symbols of absolute power, the hotline has come to occupy a unique niche in the collective unconscious somewhere between Lieutenant Uhura and the Roswell Incident. The difference being that hotlines are real. Or are they?

The first true hotline was set up by the US and USSR in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The crisis required a rapid response, but despite the fact that they ran the most technically advanced nations on earth, Kennedy and Kruschev discovered they had no means of communicating directly with each other. Shaken by how close the world had come to a nuclear war, they ordered the creation of a direct, round-the-clock link which came online on 31 August 1963.

Sadly for our mental image, that didn’t mean a red phone on the Oval Office desk. The hotline was never designed as a voice connection; instead, it carried printed messages. There were two good reasons for this. In the first place, Kennedy and Kruschev didn’t speak each other’s language, so there was always going to be a risk of mistranslation. Second, in times of heightened tension, it’s all too easy (as most of us know to our cost) to lose that caring, calm and reasonable tone – and the last person you want to upset is someone with their finger poised above a button marked ‘FIRE!’ Printed exchanges give everyone a little extra time to think.

Early versions of the White House-Kremlin hotline relied on Norwegian teletype machines, connected by cables and backed up by a radio circuit relayed through Tangiers. Cute, maybe, but not quite as clever as everyone had hoped. In the first year, a Finnish farmer ploughing his fields accidentally chopped through it; during the 1970s it caught fire in a manhole conflagration under Baltimore, then a US telephone crew inadvertently disconnected it (maybe Moscow hadn’t paid its bill). Since then, millions have been spent upgrading it using fax and fibre-optic technology. Today, the hotline operates in triplicate across two separate satellite systems backed up by a secure land line.

Presumably a similar bit of kit connects Whitehall to Washington, though when we asked Downing Street whether the Prime Minister had one and whether or not it was red, we received a crushingly frosty response: ‘We don’t discuss government communications,’ snapped some stuck-up little twerp before slamming down the phone. So much for open government.

A British Telecom spokesman did admit that hotlines might exist, before he realised his faux pas and added quickly: ‘But you’re unlikely to find out much from BT.’ Presumably he has since been executed. So now we know: hotlines are still in use, but whether they’re red – or look as swanky as they do on the set of Austin Powers – is a matter for the Official Secrets Act.

Things weren’t always quite as glamorous in the pre-hotline days. According to the Imperial War Museum, during the first years of the Second World War, Churchill and Roosevelt’s aides regularly had to spend anything up to half an hour working through an exhausting series of security hoops in order to establish that it was, in fact, the White House on the other end and not, say, Henrich Himmler.

This problem was partly alleviated when new US encryption equipment was shipped over the Atlantic in 1942. Partly because when the ripped off the gift-wrap, squealing with excitement, the equipment turned out to be the size of several elephants. Far too big to fit into Churchill’s poky bunker under the Treasury, it had to be installed in Selfridge’s basement instead. Whether shoppers in the luggage department could listen in to Roosevelt and Churchill’s tête-à-têtes is, sadly, not recorded. What we do know, however, is that Churchill’s hotline was hidden in a tiny room disguised as his private WC, complete with a lock displaying Vacant/Engaged. So whimsical. So English.

We trust that things have moved on, though today’s all-singing, all-dancing hotlines must lack the sexy menace of the red telephone that is standard issue on so many presidential film sets. In the absence of an invitation to NORAD or a peek into the Prime Minister’s inner sanctum, we’ll just have to make do with dodgy spy films and our fervent imaginations. This may be no bad thing – after all, when was the last time reality turned out to be even sexier than fantasy?