Christopher Stocks

Journalism

- Madresfield | House & Garden

- Winfield House | Gardens Illustrated

- Naming of Names | Independent on Sunday

- Tessa Kennedy | House & Garden

- USCS | Abercrombie & Fitch Magazine

- Armageddon Calling | Wallpaper

- Beverley Nichols | Gardens Illustrated

- Deep in the Forest | Tank

- Dorset | Daily Telegraph

- Peyton Skipwith | B.B,Esquire

- Seeds | Patek Philippe

- Tenants of the National Trust | NT Magazine

- Emeco | Broom chair

- Flucked | Empire

- Space Oddity | The Face

- Cleopatra | Harpers

- Pebbles | Things magazine

USCS | Abercrombie & Fitch Magazine

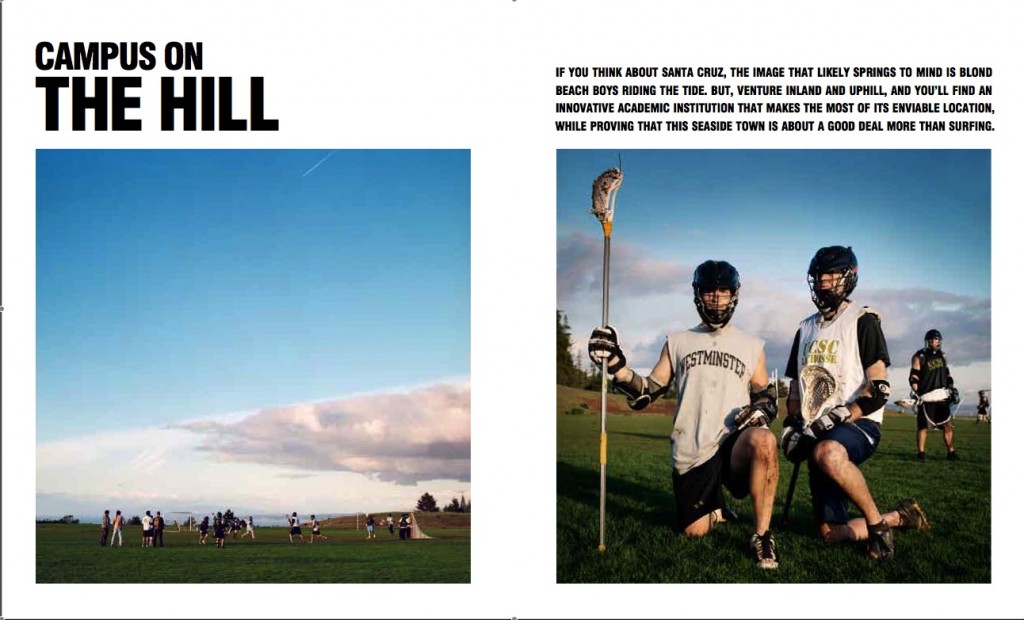

The setting is what gets most people first time round: the University of California Santa Cruz hangs high above the state’s original Surf City, with spectacular views out across the sparkling deep-blue sweep of Monterey Bay. There’s something sparkling about the air, too: mountain-fresh, crystal clean and naturally pine-scented, courtesy of a 2,000-acre campus that climbs the best part of a thousand feet from the wide-open spaces of the Great Meadow at its base to the steeply contoured foothills of the Coastal Range, densely forested with groves of coast redwoods and Douglas fir. ‘The draw for coming to UCSC is the setting,’ confirms student John Kehayias. ‘Giant redwoods, great surfing… Basically it’s a great place to get outdoors.’ So overwhelming is the natural environment that students sometimes call it ‘UCSC National Park’.

The setting is what gets most people first time round: the University of California Santa Cruz hangs high above the state’s original Surf City, with spectacular views out across the sparkling deep-blue sweep of Monterey Bay. There’s something sparkling about the air, too: mountain-fresh, crystal clean and naturally pine-scented, courtesy of a 2,000-acre campus that climbs the best part of a thousand feet from the wide-open spaces of the Great Meadow at its base to the steeply contoured foothills of the Coastal Range, densely forested with groves of coast redwoods and Douglas fir. ‘The draw for coming to UCSC is the setting,’ confirms student John Kehayias. ‘Giant redwoods, great surfing… Basically it’s a great place to get outdoors.’ So overwhelming is the natural environment that students sometimes call it ‘UCSC National Park’.

UCSC may be a large public research university with upwards of 15,000 students and 3,000 staff, but it rarely feels that way, thanks to the sprawling site and the enfolding forest, which—from ground-level at least—renders the majority of academic and residential buildings pretty much invisible. For all the brain-power being expended, the whole place has a surprisingly outdoorsy feel, not least thanks to the brilliant light and enviable climate: sunny and warm in spring and fall, with mild winters and summers whose heat is tempered by the cool coastal fogs that drift in from the bay. The campus is strung together by a complex of discreetly lit footways and winding cycle paths, which snake through the woods, arching over small ravines and taking in some pretty steep inclines on the way. Pretty much everyone walks, bikes, hitches or (this being California) skates to get where they need to be; cars are officially discouraged, though not banned altogether, and the university runs its own popular shuttle-bus service that loops around the site and links the campus to the city down below.

UCSC is different, too, from the average mid-size public university in having a collegiate structure, like Harvard or Yale, which gives it a more intimate feel than most institutions of a similar size. More practically its ten residential colleges, with their mix of apartments, dorms and shared accommodation, mean that all freshmen—or frosh as they’re called here—and second-year students can (if they choose to) live on site. It’s a flexible system that seems to work well, especially for students coming from smaller schools, though for those who’d like to be closer to the beach—sorry, would prefer to live off-campus—the University also owns two off-site accommodation blocks in downtown Santa Cruz and organises local housing.

Each college has its own individual character. You’re more likely to see students with paint-spattered jeans hanging around Porter College, say, which has an arty reputation, than at Crown, where science is high on the agenda, or Stevenson, whose professors are known for their expertise in social justice and human rights. Cowell, the oldest college, emphasises languages, classics and languages, while Merrill’s brick patios and mission-style bell-tower reflect its specialism in California Latino studies. Kresge is strong on humanities, but it also hosts what’s known as the Commuter Lounge, where non-dom students can take a break and leave their stuff, or even cook and shower. The names get less imaginative with colleges Eight (founded 1972), Nine (2000) and Ten (2002), but then they are still actively looking for kindly patrons to endow them. Though each college has its own specialisation, prospective students are welcome to apply to any of them, whatever their intended major. Another quirk of the system is that students graduate from their college, rather than just from UCSC. It might all sound rather confusing, but the collegiate set-up has two distinct built-in advantages. First, it takes what could feel like an impersonally huge institution and breaks it up into manageable, human-scale neighborhoods. And second, the fact that each college has its own individual character means that whatever your personality, there’s likely to be one college where you’ll fit in. Few things better illustrate the diversity of UCSC’s intake than three of its best-known alumni: Kent Nagano, music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra; the actress and former Victoria’s Secret model Rebecca Romijn, best known to TV viewers as Alexis Meade in Ugly Betty; and Dead Kennedys lead singer Jello Biafra. Quite a mix.

University of California Santa Cruz was founded in 1965, in a year that saw the Beatles play Shea Stadium, the assassination of Malcolm X and the first combat troops arrive in Vietnam—but don’t hold that against it. The campus, once part of the huge nineteenth-century Cowell Ranch, was laid out by arguably the twentieth century’s most influential landscape architect, Thomas Church, who was raised not far away in Oakland and studied at Berkeley, whose master plan he later oversaw. One of the first major buildings to be constructed was the high-modernist McHenry Library, still central to the campus today, which was designed by John Carl Warnecke & Associates (best known for their extraordinary, windowless AT&T Long Lines tower in Manhattan, now better known by its address, 33 Thomas Street). Its sensitive integration into the redwood forest, surrounded by carefully tended ferns, was beautifully captured in 1965 by the great nature photographer Ansel Adams: that Adams should have been persuaded to visit the site at all gives some idea of how ground-breaking the new university was considered at the time.

University of California Santa Cruz was founded in 1965, in a year that saw the Beatles play Shea Stadium, the assassination of Malcolm X and the first combat troops arrive in Vietnam—but don’t hold that against it. The campus, once part of the huge nineteenth-century Cowell Ranch, was laid out by arguably the twentieth century’s most influential landscape architect, Thomas Church, who was raised not far away in Oakland and studied at Berkeley, whose master plan he later oversaw. One of the first major buildings to be constructed was the high-modernist McHenry Library, still central to the campus today, which was designed by John Carl Warnecke & Associates (best known for their extraordinary, windowless AT&T Long Lines tower in Manhattan, now better known by its address, 33 Thomas Street). Its sensitive integration into the redwood forest, surrounded by carefully tended ferns, was beautifully captured in 1965 by the great nature photographer Ansel Adams: that Adams should have been persuaded to visit the site at all gives some idea of how ground-breaking the new university was considered at the time.

Its radical heritage as a one-time hippy hotbed has mellowed over the years, though perhaps that’s no big surprise, given the fabulous natural surroundings and Santa Cruz’s fame as a surf-and-skater paradise. Like the university itself, Santa Cruz has largely ditched its radical reputation, but it still boasts impressively high environmental credentials: starting as far back as 1980, for example, the city replaced its entire stock of street lighting with low-glare lamps in order to reduce its light pollution, which was severely restricting the work of the UCSC-administered Lick Observatory on the mountains up above. And Monterey Bay itself forms the largest marine reserve in the USA, with 4,000 square (nautical) miles of protected waters offering sanctuary to a fantastic range of marine life, including gray and humpback whales. The city, which also hosts boardshort-to-wetsuits behemoth O’Neill and Santa Cruz Surfboards, boasts thirty miles of beaches and no less than eleven world-class surf breaks. So while UCSC may be rightly proud of its academic strengths, it’s a fair bet that a big draw for many applicants is its 50-metre pool and excellent athletic facilities, not to mention the daily surf classes and extensive recreation programs, which take in everything from whale watching to wine appreciation.

Yet there’s more to Santa Cruz than its enviable climate and idyllic setting. Academic standards are high, and in several areas UCSC has an international reputation. Its space sciences faculty is particularly notable, as befits a campus with strong links to the US space program—and not just historical links either: in 2003 UCSC launched a joint venture with NASA’s Ames Research Center south of Palo Alto, which will eventually form an off-site mini-university of its own, complete with a slated 2,000 full-time students. As befits a large public university, UCSC offers a wide mix of subjects, and its 60 major courses take in everything from literature to linguistics and chemistry to computer science, but there are headline specialisms too, particularly in engineering, economics and bioinformatics.

Given that the campus looks out across Monterey Bay, it will come as no surprise that its Institute of Marine Sciences should be at the forefront of international research; but at first glance its strength in pure science and technology seems less easy to explain. The answer lies over the other side of the redwood forests and the 3,000-foot coastal range. Just 35 miles away is San Jose, capital of Silicon Valley, which means that, though they’re not exactly in its backyard, UCSC can count Google, Apple, Adobe Systems and eBay among its neighbours. Classes tend to be small, with plenty of one-on-one tuition. The art program is popular, with graduate programs in digital arts and new media. Meanwhile the Program in Community and Agroecology (PICA), based in Lower Quarry Village, is renowned for its pioneering work in organic farming and horticulture, with a history stretching back to the early 1970s. Students live, work and prepare food together in the Village, gaining practical experience on the university’s own organic farm. The program is widely credited for helping to power up the whole organic movement in California and beyond, and it’s no coincidence that the area is noted for its organic wineries and farms.

Is there a catch? Not really, though as a state-funded public university, it helps to be a Californian citizen: course fees are about half what non-Californian students pay. But the real elephant under the room is something that lies near the ridge of the Santa Cruz mountains, just a few miles inland. It’s so familiar that few Californians even think to mention it, though the university has been quietly spending millions of dollars on its behalf, upgrading existing buildings and ensuring that new ones (such as the $75 million McHenry Library extension, scheduled to open in 2009) have plenty of… well, let’s call it seismic capacity. Yep, you’ve guessed it: we’re talking the San Andreas Fault. Still, there may be decades yet before the earth moves again—in the meantime, there can’t be many other places that offer quite such a seductive mix of surf culture and astrophysics.